Thanks to Watcher – and Santanta – for bringing this story to our attention. It deserves a wider airing and I have lifted the following Independent obituary, by Rupert Cornwall off the Internet for your benefit.

Rupert Cornwell

Irena Krzyzanowska, social worker: born Otwock,

Celebrity befalls heroes on the most random basis, as the story of Irena Sendlerowa demonstrates. Oskar Schindler was a businessman and one-time Nazi, who saved some 1,200 Jews by having them work in his factories in wartime

Yet it was Schindler, not her, who in 1993 was the subject of an Oscar-winning movie by Steven Spielberg. Only six years later did a

The result was Life in a Jar, a 10-minute play which won a school competition in

The daughter of a doctor who died of typhoid while treating a local outbreak of the disease when she was only eight, Irena Krzyzanowska (as she was born) inherited her father’s sense of duty towards those in distress. “I was taught that when you see a person drowning,” she told an interviewer years later, “you must jump into the water to save them, whether you can swim or not.”

Before the war, she had married Mieczyslaw Sendlerow, and when the Germans invaded

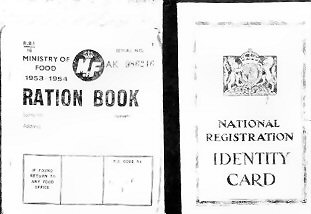

Sendlerowa joined Zegota, the code name for the Council for Aid to Jews in Occupied Poland, which forged birth certificates and other documents to give Jews new Aryan identities. She was given the code name Jolanta, and the mission of smuggling children trapped in the ghetto to safety.

As an employee of the social services department, she was able to pose as a nurse, armed with a fake permit that allowed her into the ghetto to check for outbreaks of typhus, which the Germans feared might spread through the entire city. During her visits she wore a Star of David so as not to attract attention to herself.

Over some three years, she and her co-workers persuaded parents and grandparents to hand over an estimated 2,500 babies and children in all, giving them a chance to live. They were taken out in sacks, baskets, hidden under cartloads of goods, even in coffins. Once in “Aryan”

Sendlerowa was party to heartbreaking scenes that she would never forget. “One mother. . . wanted a child to leave the ghetto, while the father did not,” she said of one family. “They asked what the guarantee was. But what kind of guarantee could I give them?” Indeed, she could not even be sure she would get past the guards on her way out. All she could promise another mother who wept as she gave over her son, was that “if he stays with you, he will die.”

Irena Sendlerowa tried to record the identity of every child she brought out, writing down the original Jewish name as well as his or her new Christian name and address. She buried the sheets of paper with the names in jars under an apple tree in a friend’s garden – hence the title of the schoolgirls’ play in

But on 20 October 1943, Sendlerowa herself was arrested, after her name had been given by an associate who had been captured and tortured. She too was subjected to appalling torture that left her permanently disabled. But Sendlerowa divulged nothing and in January 1944 she was sentenced to be executed. And according to Nazi records, she was indeed put to death – except that Zegota somehow managed to bribe a guard who led her from prison, supposedly to be shot. Instead he told her, “Run.” She did, and escaped to safety.

A year later

After the war, Sendlerowa returned to her work as a social welfare official, continuing to help some of the children she had rescued. She refused to consider herself a hero. “Heroes do extraordinary things,” she said. “What I did was not an extraordinary thing. It was normal.”

But her courage was extraordinary enough for the Yad Vashem holocaust memorial in

Only in 1999 did the teacher in