The houses about Drumbally were scattered – I doubt if there were more than a dozen in a radius of a mile – and there wasn’t much by way of entertainment available. What there was, was talk.

Month: October 2008

Shane the Proud is rampant

Shane O’Neill’s taking of Newry and Dundrum was just the start of a widespread campaign he waged in

In October Nicholas Bagenal was restored to the position of

On 12th November the Queen instructed

In a letter written by Bagenal from

Shane was in possession of all the countries from Sligo to Carrickfergus, from there to Carlingford and south to

All this was despite the Queen’s Deputy’s efforts to quell him.

And he had forged a sure bond with

…. more later ….

Shane O’Neill’s continuing campaigns

The history of

In the end it was the McDonnells of Antrim who were to be his undoing.

In the meantime the articles of peace concluded at

He observed the peace terms only fitfully and selectively and the English government was soon plotting against him again.

Shane was harrying his inferior chieftains (the Armagh O’Neill’s castle at Glassdrummond was taken and fired, for example) and harassed the garrison of

From time to time Shane concluded further pacts with the English: on 18th November 1563 at Benburb he agreed to wage war on the Queen’s enemies while he further won the right to the title of The O’Neill under Con’s patent. A memorandum in reference to this agreement signed by O’Neill is dated 28th February 1564 at Fedan.

This is evidence that Shane O’Neill possessed a castle at Fathom just a few miles from Bagenal’s house at Newry. Bagenal may have even resided there from time to time but likely in Shane’s absence on his many conflicts.

For example in early 1565 O’Neill confronted the Antrim Scots on their home territory, eventually routing them and taking two leaders, James and Sorley Boy MacDonnell prisoner. This was also in pursuit of his promise to wage war on the Queen’s enemies.

Again on 25th August of that year Shane wrote, from Fathom, to the Privy Council informing them of the success of those operations.

Ironically, in that same month Shane swooped from Fathom to take back the monastic seat – the old Abbey – that even in his memory had been seized by the English adventurer Nicholas Bagenal from the holy monks who had built it and possessed it and ministered to their people there for ages past (more than four hundred years).

Bagenal appears not to have been at home at the time.

To consolidate his position Shane went on also to seize the

Despite this clear signal of Shane’s intent to consolidate his power base throughout

Shane rampant …

… more later …

Drumbally: neighbours

The river bounded the other side of the field where our house was located at Drumbally. It was about 20 feet across and about five feet deep between steep sides six feet above the level of the water. Two sturdy planks spanned the gap. The whole was about a yard wide with no side rails or rope support.

Provincial Governors proposed

The new Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603) was as much concerned with the Scots of Antrim as with Shane. In the instructions given to

‘to devise in the mean season how that part which is called Lecale and the Newery and Carlingford may be stayed and preserved from the possession of the Scots ..’. Clearly the new, young English Queen had no confidence in Mr Bagenal’s ability to defend his ‘possessions’.

A rupture soon occurred between Shane and the Government and in July 1561

It was the failure of these attempts to subjugate him that drove the English to terms with Shane and occasioned his visit to

In his absence his followers plundered Bagenal’s territories without mercy.

In writing to Cecil, the Secretary of State on 23rd April Bagenal complains loudly: he alleges that his lands, which when he was

Desmond Rebellions

What is erroneously referred to in English history as the Desmond Rebellions occurred in (first) 1569-1573 and (second) 1579-1583 in

Unwilling or unable to pronounce the correct name of the area – ‘Deasmumhain’, or ‘

The provinces of

Had these houses and their leaders – with other Old English and Irish – acted in concert, they might well have survived the onslaught to come but, if anything, they were more antagonistic to one another than to the English authorities who wished to suppress them. As often, the English exploited this internecine antipathy.

As we have learned already in relation to Bagenal in the North, the English planned to replace local leaders with provincial presidents (military governors, in effect) and it was in pursuit of this planned policy that Lord Deputy Sidney undertook to confront the Geraldines (the Fitzgerald leaders of Munster) and the Ormondes (Butlers).

The ‘rebellions’ were primarily about the independence of lords from their monarch but as they progressed they had an increasingly important element of religious conflict. This contributed to the heightened brutality of the subsequent repression. The result of the rebellions was the destruction of the Desmond dynasty and the subsequent plantation of

The local dynasties saw the presidencies as intrusions into their sphere of influence and into their traditional violent competition with each other. This had seen the

Queen Elizabeth summoned the heads of both houses to

This removed the natural leadership of the Munster Geraldines and left the Desmond Earldom in the hands of a soldier, James Maurice Fitzgerald, the “captain general” of the Desmond military. Fitzmaurice perceived no role for himself in the proposed new order in

A factor that drew wider support for Fitzmaurice was the prospect of land confiscations, which had been mooted by Sidney and Peter Carew, an English colonist. This ensured Fitzmaurice the support of important clans, notably MacCarthy Mor, O’Sullivan Beare and O’Keefe and, indeed two prominent

Fitzmaurice himself had lost the land he had held at Kerricurrihy in

Fitzmaurice however had wider aims than simply the recovery of Fitzgerald supremacy. Before the rebellion, he secretly sent Maurice MacGibbon Catholic Archbishop of Cashel to seek military aid from King Philip II of

Fitzmaurice launched his insurrection in June 1569 by attacking the English colony at Kerrycurihy before attacking

In response,

Together, Ormonde, Sidney and Humphery Gilbert, appointed as governor of

As individual lords felt compelled to retire to defend their own territories under this onslaught, Fitzmaurice’s forces broke up. Gilbert in particular was notorious for the terror tactics he employed, killing civilians at random and setting up a corridor of severed heads at the entrance to his camps.

In late 1569 a similar but shorter insurrection broke out in

In February 1571, John Perrot was made Lord President of

Fitzmaurice finally submitted on February 23, 1573, having negotiated a pardon for his life. However in 1574, he again became landless and in 1575 he sailed to

Gerald Fitzgerald, Earl of Desmond, and his brother John were released from prison to stabilise the situation and to reconstruct their shattered territory. Under a new settlement imposed after the rebellion, known as “composition”, the Desmond’s military forces were limited by law to just 20 horsemen and their tenants made to pay rent to them rather supply military service or to quarter their soldiers.

Perhaps the biggest winner of the first Desmond Rebellion was the Earl of Ormonde, who established himself as loyal to the English Crown and as the most powerful lord in the south of

Although all of the local chiefs had submitted by the end of the rebellion, the methods used to suppress it provoked long-lasting resentment, especially among the Irish mercenaries, gall oglaigh or “gallowglass” as the English termed them, who had rallied to Fitzmaurice.

William Drury, the new Lord President of

Fitzmaurice had deliberately emphasized the Gaelic character of the rebellion, wearing the Irish dress, speaking only Irish and referring to himself as the captain (taoiseach) of the Geraldines.

Finally, Irish landowners continued to be threatened by the arrival of English colonists. All of these factors meant that, when Fitzmaurice returned from continental Europe to start a new rebellion, there were plenty of discontented people in

The second Desmond rebellion was sparked when James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald launched an invasion of

Fitzmaurice landed at Smerwick, near Dingle on July 18, 1579 with a small force of Spanish and Italian troops. He was joined in rebellion on August 1 by John of Desmond, a brother of the Earl, who had a large following among his kinsmen and the disaffected swordsmen of

Gerald, the Earl of Desmond, initially resisted the call of the rebels and tried to remain neutral but joined in once the authorities proclaimed him a traitor. The Earl joined the rebellion by sacking the towns of Youghal (on November 13) and Kinsale, and devastated the country of the English and their allies.

However by the summer of 1580 English troops under William Pelham and locally raised Irish forces under the Earl of Ormonde succeeded in bringing the rebellion under control, re-taking the south coast, destroying the lands of the Desmonds and their allies in the process, and killing their tenants. By capturing Carrigafoyle at Easter 1580, the principal Desmond castle at the mouth of Shannon river, they cut off the Geraldine forces from the rest of the country and prevented a landing of foreign troops into the main

However, in July 1580, the rebellion spread to

Shane O’Neill in control

When

First he subjected the local chiefs of our area (O’Hanlon and Magennis) to his power and made them his uriaghts.

Where Bagenal was at this time we are uncertain, but as he later took frequent refuge in Greencastle – which he seemed to prefer as a home to Newry – it is not unlikely that he was there.

The English were not to take it all lying down. On 1st February a commission was granted to William Ashely and Thomas Bramley to execute martial law in the territories of Newry, Mourne and Cooley. As Small (in his ‘Sketch’) remarked, ‘such arbitrary proceedings cannot have tended by any means to pacify the country or reconcile it with English rule’.

Nor did it work.

The government was compelled to send Sir Henry Sidney with an army to

Avoiding open conflict on this occasion, Shane invited

For the time being Shane O’Neill retained hegemony in his own domain.

Bagenal remained slighted. He probably chose not to have O’Neill look down in dominating fashion from his castle at Fathom: we can reasonably surmise that he remained in retreat elsewhere – Greencastle being the most likely place.

… Desmond rebellions …

… more later ….

Crossmaglen, 1930s

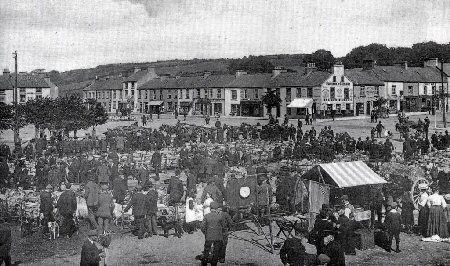

Crossmaglen, or Cross as it is better known in the area, was the largest village in that part of the County. Its principal feature was its large square, reputedly the largest in

There was the chapel, school, police barracks, picture house, dance hall and football pitch. The village was not electrified until the 1950’s although the cinema had a generator.

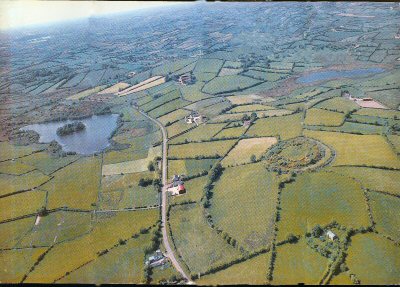

Drumbally, comprising 265 acres, lies two miles from Crossmaglen and three miles from the borders with Co. Louth and Co. Monaghan. Drumbally lies on a large drumlin and from the top on a clear day, flat countryside stretches south for many miles into Co Louth. In common with most of the rest of the country, the townland suffered a decline in population during and after the Great Famine 1845 – 1848. From Census returns we know that from 144 people in 75 dwellings in 1841, the population steadily declined, by 1951, to 37 people in 14 dwellings – a 74% reduction.

At the time of the 1901 Census (the first one for which complete documentation survives) 11 of the 17 households contained at least one native Irish speaker – 13 in all. The average age of the group was 61; eldest 80, youngest 40. Drumbally had a significantly higher proportion of Irish speakers than the (civil) parish as a whole where 785 of 5249 (15%) spoke the language. When I arrived, 37 years later, most, if not all of this group would have passed on, taking with them a whole tradition.

The house where I was born and lived in until 1952, was a slated single storey, two-roomed cottage 50 yards down a sunken lane at the foot of Drumbally hill. It belonged to “James Pat” McShane who had emigrated. The rent was 1s 6d a week. There was a shed, a “street” (a clear area, or yard, in front of the house) and two “gardens”, one of which my father planted out in potatoes and vegetables each year.

When it rained, the water rushing down the lane in a torrent was an endless source of joy to me in setting up dams, making diversionary channels and generally getting wet through. I never remember the water as cold – it always seemed warm and fresh, with a feeling of newness, and promise, as it first rushed, and then trickled, over the stones. In the hard winter of 1947 the lane filled with snow and my father spent a whole day digging up to the road.

… more later …

For those of you who tire of my drip-feed methods (the Newry Journal style from the beginning) – you may read Pat’s memoirs complete here

… History: Town of Crossmaglen? …