Thomas Russell – the man from God-knows-where – was a United Irishman leader, a friend of Tone and Emmett, who organised Co Down (the location of Florence Wilson’s poem), was arrested and gaoled before the ’98 Rebellion but, after his release in 1802 he organised the North in Robert Emmett’s ill-fated 1803 uprising.

The first part of the poem is set in Winter 1795, the latter in Autumn 1803.

The implication in the beginning is that Russell was unaware he was among sympathisers when he stopped at the tavern to shelter from the snow storm – they didn’t after all, ‘ride different ways’. ‘

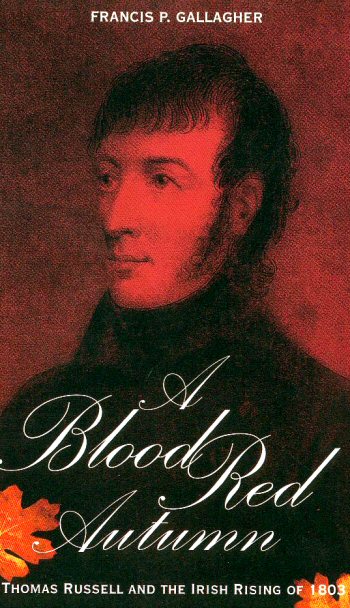

The recently published book, ‘A Blood Red Autumn – Thomas Russell and the Irish Rising of 1803’ (Fairythorn 2003) by local man Francis P Gallagher has done much to enlighten us all on the life and times of this great and brave leader, who championed the loftiest of ideals.

Into our townlan’ on a night of snow

Rode a man from God-knows-where

None of us bade him stay or go

Nor deemed him friend, nor damned him foe,

But we stabled his big roan mare:

For in our townlan’ we’re decent folk,

And if he didn’t speak, why none of us spoke,

And we sat till the fire burned low.

We’re a civil sort in our wee place,

So we made the circle wide

Round Andy Lemon’s cheerful blaze

And wished the man his length o’ days

And a good end to his ride.

He smiled in under his slouchy hat –

Says he, ‘There’s a bit of a joke in that,

For we ride in different ways’.

The whiles we smoked we watched him stare,

From his seat fornenst the glow.

I nudged Joe Moore, ‘You wouldn’t dare

To ask him who he’s for meeting there,

And how far he has got to go.’

But Joe wouldn’t dare, nor Wully Scott,

And he took no drink – neither cold nor hot –

This man from God-knows-where.

It was closin’ time, and late forebye

When us ones braved the air –

I never saw worse (may I live or die)

Than the sleet that night, an’ I says, says I,

‘You’ll find he’s for stoppin’ there.’

But at screek o’ day, through the gable pane,

I watched him spur in the peltin’ rain,

And I juked from his rovin’ eye.

Two winters more, then the Trouble Year

When the best that a man could feel

Was the pike he kept in hidlin’s near,

Till the blood of hate an’ the blood of fear

Would be redder nor rust on the steel.

Us ones quet from mindin’ the farms,

Let them take what we gave wi’ the weight o’ our arms,

From Saintfield to Kilkeel.

In the time o’ the Hurry, we had no lead –

We all of us fought with the rest –

An’ if e’er a one shook like the tremblin’ reed,

None of us gave neither hint nor heed,

Nor ever even’d we’d guessed.

We men of the North had a word to say,

An’ we said it then, in our own dour way,

An’ we spoke as we thought was best.

All

For the stan’in’ crops on the lan’

Many’s the sweetheart and many’s the bride

Would liefer ha’ gone till where he died,

An’ ha’ murned her lone by her man.

But us ones weathered the thick of it

And we used to dander along, and sit

In Andy’s, side by side.

What with discourse goin’ to and fro

The night would be wearing thin,

Yet never so late when we rose to go

But someone would say, ‘Do ye min’ thon snow,

An’ the man who came wanderin’ in?’

And we be to fall to the talk again,

If by any chance he was one o’ them –

The man who went like the win’.

Well ’twas getting on past the heat o’ the year

When I rode to

I sold as I could (The dealers were near –

Only three pounds eight for the Innis steer,

An’ nothin’ at all for the mare!)

I met McKee in the throng o’ the street,

Says he, ‘The grass has grown under our feet

Since they hanged young

And he told that Boney had promised help

To a man in

Says he, ‘If ye’ve laid the pike on the shelf,

Ye’d better go home hot-fut by yerself,

An’ polish the old girl down.’

So by Comber road I trotted the gray

An’ never cut corn until Killyleagh

Stood plain on the risin’ groun’.

For a wheen o’ days we sat waitin’ the word

To rise an go at it like men.

But no French ships sailed into

And we heard the black news on a harvest day

That the cause was lost again:

And Joey and me, and Wully Boy Scott

We agreed to ourselves we’d as lief as not

Ha’ been found in the thick o’ the slain.

By Downpatrick gaol I was bound to fare

On a day I’ll remember, feth;

For when I came to the prison square

The people were waiting in hundreds there,

An’ you wouldn’t hear stir nor breath!

For the sodgers were standing, grim an’ tall,

Round a scaffold built there fornent the wall,

An’ a man stepped out for death!

I was brave an’ near the edge o’ the throng,

Yet I knowed the face again,

An’ I knowed the set, an’ I knowed the walk,

An’ the sound of his strange up-country talk,

For he spoke out right an’ plain.

Then he bowed his head to the swinging rope,

While I said, ‘Please God’ to his dying hope,

And ‘Amen’ to his dying prayer,

That the Wrong would cease, and the Right prevail

For the man that they hanged at Downpatrick gaol

Was the man from God-knows-where!

.. Eliza Goddard …

… Magennis Grave, Clonduff …