The boy walked down

His grandmother had died on Christmas Eve and was buried behind that wall. He could see

Looking back up the hill, the boy noticed that the bunting strung back and forth between the houses on either side of the street was hanging absolutely still. There were little Union Jacks and triangles in red, white and blue. Above his head, King Billy on a white horse was supported by two steel wires. His right arm was pointing towards the cloudless blue sky, his sword slightly bent near the tip. In the middle of the junction where

Besides, maybe they were all making it up. Surely his da and everybody else would know if that kind of thing was going on. Anyway, why would a man do that?

He knew that women did it. At least, he knew one woman who did it. Mrs Armstrong did it. Every time she came to the house to see his aunt, he tried his best not to be the one who answered the door. He wished the weather could always be hot so that the door would be open and she could walk straight in. Everybody always just walked straight into each other’s house, calling – ‘Are yis in?’ by way of warning. But when it was cold or raining, the doors were shut, and he dreaded the sound of the knocker when he thought it was Mrs Armstrong. He would renew his concentration on the ‘Beano’ or the ‘Dandy’, hoping that someone else would open the door, but it was always,

‘Get the door, Jack’.

He would unlatch the top of the half-door and there she would be. When he unbolted the bottom section of the door, she would bustle into the small hallway in a second.

‘Ah, those eyes’ll break many a heart whin you grow up’, she always said, her hand reaching for the front of his trousers. He would wriggle and push at her hand, but now and again she made contact with his doodle and his face would flush. What was even worse sometimes was that later he would think of her touch and her big breasts and feel a strange pleasure that he could not understand.

But at least men and women did things like that – he had seen it in the Regal picture-house on Saturday mornings – those boring bits in the cowboy films when Randolph Scott or Alan Ladd would stop fighting Indians to kiss women. But a man with boys? That couldn’t happen, could it? He trembled as he walked to the pub door. Doing what Jemmy had said, he knocked with his knuckles on the frosted glass panel of the inside door, pushed it open and went in.

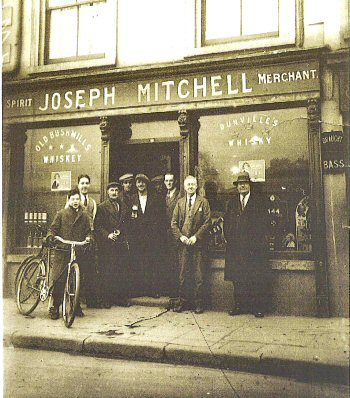

The bar was in front of him, only about three yards long. On the wall behind it there were three shelves with bottles of Jamesons, Bushmills and Black Bush whiskeys on the top one. The middle shelf held Paddys, White Horse and Stewart’s Cream of the Barley, and the bottom had a row of Captain Morgan’s and Lamb’s rum and Gordon’s gin. There were three little silver cups without handles. At the end of the counter there was a figurine of a striding man with a red coat, a black top hat and a walking stick. ‘Johnny Walker’ was printed on the base. Beside it was an electric kettle plugged into a socket on the wall. It was the first electric kettle he had seen outside of a shop window.

To the right was a doorway into a small room with a tiny window giving on to

The ceiling and walls had originally been painted cream, but were now heavily discoloured by a uniform dark brown staining. Years of cigarette smoke. The ceiling in his granny’s tiny kitchen was that colour. He started at the sudden hissing sound of water and realised that a urinal had just been flushed. It sounded like the automatic yoke they used in the lavatories at the picture-house. When he suddenly called ‘Hullo!’ it emerged as a croak. He licked his lips and did better the second time. The rattling stopped and he heard footsteps. A shadow appeared on the floor to his right and a man followed it into the bar. The boy took an uncertain step backwards and felt his buttocks touch the door.

‘Yis-yis…. whaddya want?’

The boy wasn’t sure what he had said. He stared at the man and tried to swallow but his mouth was too dry. The man was short and podgy. Over a white shirt with a grubby collar he wore a grey woollen pullover which had Guinness stains on the front and what looked like dried bits of fried-egg yoke. He had baggy, dark- grey flannel trousers and black leather shoes which hadn’t been polished for a long time. His black hair was flecked with grey and had the shiny plastered-down look of a heavy layer of Brylcreem. He gave off a faint whiff of perfume. He had small eyes behind horn-rimmed glasses. His lips were thin.

‘Spake up! Wha canna do-ye for?’

The boy suddenly understood. If you really concentrated, you could understand. He placed the bag carefully between his feet and fumbled in his trouser pocket. He pulled out the money and the note and held them out hesitantly, trembling slightly as he did so. As the man took them the boy noticed that his hands were delicate and long-fingered, but his nails were dirty.

‘Who are these fer?’

The boy gulped and said, ‘Jemmy – Jemmy McCulla’.

‘Rightye-be’, the man answered. ‘Are them empties in the beg?’

‘Aye, six’.

He leaned over and picked up the carrier bag. The man took it and turned to the counter. He took the bottles out one by one and placed them in a neat row along the side, by the electric kettle. He turned back and said curtly,

‘Tellim ta washem out the nixtime’. The boy nodded and waited.

The man lifted the hinged end-section of the counter and walked behind the bar. He disappeared momentarily, hunkering down. His hand appeared and placed first one and then another bottle of Guinness on the counter-top. He stood up and said,

‘Yecan puttem in the beg yerself’.

He pressed a key on the till below the shelves. It clattered open with a ding! He dropped the two shilling pieces into the tray and then eased out a sixpenny piece in a stroking motion with four fingers of his left hand. He slammed the drawer shut and turned to lean on the counter.

‘There’s yer tanner’. He snapped the coin down sharply. The boy didn’t move.

‘You’re Jemmy’s son Jack’.

It wasn’t a question. The boy breathed nervously. The man knew who he was. How did he know?

‘Ah know all yer family. Ah’ve seen you in the street with Bobby Henderson’.

The boy’s heart pounded suddenly. Bobby was one of the boys who had told him about Ernie. God! If Bobby has let this man touch him, he might think I’ll let him do it too. He felt himself go red in the face. The man looked at him and suddenly seemed to be a little less sharp.

‘D’ye wanna drinka lemonade?’

Without waiting for an answer, he leaned down and took a tumbler from beneath the counter. He picked up a bottle of Cantrell and Cochrane lemonade from the surface behind him and unscrewed the metal cap. The lemonade foamed into the glass until it was nearly full of froth. Ernie waited until the bubbles had subsided and then slowly topped the glass up until it was brimming with liquid. He placed it at the front edge of the counter and screwed the cap back on tightly. He replaced the bottle and turned back to lean on the counter again.

The boy licked his lips again and picked up the glass. He raised it slowly to his mouth and gingerly took a sip. It tasted good. He took a bigger swig and felt embarrassed when he couldn’t control a sudden belch.

‘Ah, sure that show’s yer injoyin it’, the man said.

He seemed to be much more friendly now.

‘What school deya go ta?

‘

‘An what age areya? Nine?’ The boy nodded.

‘Here, gimme the beg an ah’ll put the bottlesinit fer ya’.

The boy handed him the bag and the man clinked the two bottles into it on the counter. They had Portnamon Mineral Water labels. The boy suddenly remembered.

‘Jemmy sez have ye got Hugh Connor’s’.

‘No, ah’m all outta that until Monday. Why does ivrybody want Hughie Conner’s? Sure there’s no difference’.

That’s not what my uncles say, the boy thought. They swear that Portnamon Minerals is always flat. He felt relaxed now. This wasn’t so bad. Ernie seemed friendly enough, and it was nice to get a free lemonade. The boys had pulled his leg with their stories.

The man suddenly turned around and punched a key on the till. He took something out and closed the drawer again. A moment later, he placed a two-bob bit on the counter, holding it vertical with the tip of the index finger of his right hand. He carefully formed an ‘O’ with the tip of his left middle finger tucked into the first joint of his left thumb. He flicked his middle finger against the edge of the coin, quickly raising his other hand out of the way. They both watched as the coin spun rapidly, then more and more slowly, finally wobbling to a halt with a light clatter. The boy looked at it and saw the bearded face of King George the Fifth. Ernie picked up the coin and flicked it into the air. He caught it as it fell and slapped it down on the counter.

‘D’ye read comics?’ he demanded. Now it was his turn to lick his lips. He glanced at the door behind the boy and said,

‘Ye could buy a lotta comics with half-a-crown’.

There were little bubbles of spittle at the corners of his mouth. The boy stared at him. He didn’t know what to say. He was suddenly aware that the man’s breathing had changed. It was deeper. His left hand had disappeared behind the counter. He was staring at the boy, but in a strange way; his eyes seemed to be looking beyond him. His lips parted slightly and the boy could just see the tip of his tongue. To his alarm, the boy now felt strangely unsettled.

He took a gulp of lemonade. He had a sudden image of Mrs Armstrong’s breasts. He felt himself stiffening. He thought he knew what was happening, but he wasn’t certain. Then the man grunted softly and leaned heavily against the back of the counter. The boy took a hasty step backward, certain that the man was about to tumble right over on top of him. He felt the urge to run but stayed where he was. He couldn’t take his eyes off the man.

Ernie had gone red in the face. Gradually, his agitation subsided. The boy clutched his glass and waited. Then Ernie pushed his weight off the counter and said,

‘Ah’ve got work ta do. Tell yer uncle Jemmy ta wash them bottles the nixtime’.

He walked out from behind the bar and disappeared towards the lavatories.

The boy was calm now. He took the carrier bag and turned towards the door. As his hand reached for the door-handle, he suddenly stopped, turned and stepped back to the counter. King George the Fifth was staring towards the electric kettle. For a moment the boy hovered, uncertain. Then, he reached out and picked up the coin. He dropped it into his left-hand trouser pocket. He opened the door and walked out into the sunshine, blinking. He could feel sweat trickling down his back under his shirt. He turned right towards the corner.

He wasn’t entirely sure what had happened, but the coin was heavy against his thigh. Something told him that he had somehow earned it.