Folklore

Mayflower Dancing

Pearls & Gold

Maybe the Laziness’ll lave ye!

Ye cleared it well, Dan!

Burial Customs

‘On the day of a funeral, a large concourse of people assembles who are plied with spirits, generally two glasses. The corpse is then placed on the bier which is covered with a pall. It is then hoisted on men’s shoulders and they are followed by the keeners who intone alternatively all the way to the burial place. The bearers are relieved frequently by others.

It often happens that if another funeral should appear from a different direction that a scene of competition commences for precedence. Sometimes it turns into strife or riot. In explanation of this custom we have heard it said that when graveyards were not hedged about, it was usual to post a sentinel at night to watch the graves from wild beasts and every other thing to which they might be exposed. (Editor: perhaps the sensibilities of his religious office caused Rev Nelson not to mention the greatest danger from grave-robbers). This office fell to the relatives of those who had been last buried in the cemetery.’ [Nelson, 1840]

Funeral Customs

‘The wakes and funerals of the Irish,’ wrote Rev Nelson in his History of Creggan Parish (1840), ‘are no less interesting. On death the corpse is carefully washed over and, if an adult, dressed in the usual manner. It is placed under board, as it is called, that is, on a long table (often provided by the funeral undertakers who keep one for the purpose) about six foot long and two foot wide but when this cannot be got, two small tables pushed together and draped with a white sheet. The corpse too is covered in a white sheet as is the wall at its head. To the latter are attached great quantities of emblematic pictures of crucifixion, resurrection etc. The table under which the corpse is laid is covered with candlesticks varying in number according to the circumstances and respectability of the deceased. The number is always odd and varies from three to thirteen.

The Rhymers or Keeners, mostly women, are sent for from a considerable distance to perform the funeral rites. Arriving at the house they partake of some refreshment and a glass of whiskey (Are these things different? Ed) then the females are arranged into two divisions, one on each side of the corpse. One of the Keeners then begins her lamentation in Irish, expressing some of either the good or the bad qualities of the deceased, or a number of foolish rhetorical questions such as, ‘Why did you die?’ or ‘Did you not like the world?’ The Keenagh or cry then goes up and all join in. The Rhymers on the other side then begins her lament and is joined in like manner by the rest, the one praising, the other disparaging the corpse.

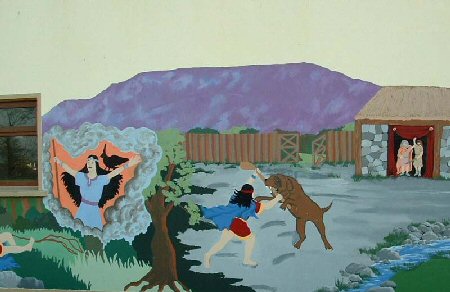

Mayday

Tomorrow week [I write on Fri 23 April] is Mayday, traditionally one of the chief dates in the Irish calendar of olden customs.

Willy the Wisp

I’ve told you about Geordie-Look-Up and about Jonny-Go-Slap. One of these days I’ll tell you about Johnny-The-Go. But today’s story is about Willie The Wisp.

Now these new-fangled scientists would tell you of a marsh phenomenon known as Will O’ The Wisp where decaying matter gives off methane gas that occasionally catches fire to emit an eerie light. Never listen! It happened this way.